Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| United States of America |

|---|

This article is part of the series:

|

| Original text of the Constitution |

Preamble

Articles of the Constitution |

| Amendments to the Constitution |

|

Subsequent Amendments

|

| Full text of the Constitution |

Other countries · Law Portal |

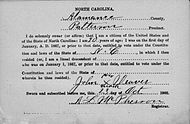

The Fifteenth Amendment (Amendment XV) to the United States Constitution prohibits each government in the United States from denying a citizen theright to vote based on that citizen's "race, color, or previous condition of servitude" (for example, slavery). It was ratified on February 3, 1870.

The Fifteenth Amendment is one of the Reconstruction Amendments.

Contents[hide] |

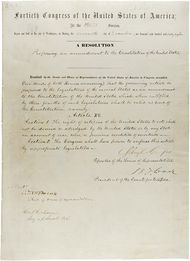

[edit]Text

-

- Section 1. The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

-

- Section 2. The Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.[1]

[edit]History

| This section needs additionalcitations for verification.(January 2009) |

The Fifteenth Amendment is the third of the Reconstruction Amendments. This amendment prohibits the states and the federal government from using a citizen's race (this applies to all races),[2] color or previous status as a slave as a voting qualification. The North Carolina Supreme Court upheld this right of free men of color to vote; in response, amendments to the North Carolina Constitution removed the right in 1835.[3] Granting free men of color the right to vote could be seen as giving them the rights of citizens, an argument explicitly made by Justice Curtis's dissent in Dred Scott v. Sandford:[4]

Of this there can be no doubt. At the time of the ratification of the Articles of Confederation, all free native-born inhabitants of the States of New Hampshire, Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey and North Carolina, though descended from African slaves, were not only citizens of those States, but such of them as had the other necessary qualifications possessed the franchise of electors, on equal terms with other citizens.

Both the final House and Senate versions of the amendment broadly protected the right of citizens to vote and to hold office.[5] The final House version read:

The right of citizens of the United States to vote and hold office shall not be denied or abridged by any State on the account of race, color, nativity, property, creed or previous condition of servitude.[6]

Likewise, the final Senate version read:

No discrimination in the exercise by any citizen of the United States of the elective franchise, or in the privilege of holding office, shall in any State be based upon race, color or previous condition of said citizen or his ancestors.[6]

However, both versions of the amendment posed serious challenges in being ratified by three-fourths of the states.[7] A handful of states still required voters and candidates to be Christian. Southern Republicans saw a value in continuing loyalty tests, which the Reconstruction state governments used to limit the influence of ex-Confederates; and Democrats in some Northern and Western states wanted to continue to be able to disenfranchise non-native Irish and Chinese.[8]

To increase chances of ratification, the amendment was revised in a conference committee to remove any reference to holding office and only prohibited discrimination based on race, color or previous condition of servitude. Yet, despite these changes, ratification of the amendment was still in some doubt. Overall, the writers of the Fifteenth Amendment produced three different versions of the document. The first of these prohibited states from denying citizens the vote because of their race, color, or the previous experience of being a slave. The second version prevented states from denying the vote to anyone based on literacy, property, or the circumstances of their birth. The third version stated plainly and directly that all male citizens who were 21 or older had the right to vote. Congress decided that using the first version would be the most effective and most likely to pass because it was the most moderate.[9]

Virginia, Mississippi, Texas and Georgia, ratified the amendment, because it was a precondition to them having congressional representation. Nevada ratified the amendment, but only after being reassured by Senator William Morris Stewart that the amendment would not preclude prohibiting the Chinese and Irish immigrants from voting.[10] California and Oregon both opposed the measure out of fear of Chinese immigrants, New York initially ratified the amendment, but legislators later attempted to rescind the ratification, a controversial decision that might have resulted in a court challenge, but for the fact that on March 30, 1870, enough states had ratified the amendment for it to become part of the Constitution.

Thomas Mundy Peterson was the first African American to vote after the amendment's adoption. Peterson cast his ballot in an election over whether to revise the city of Perth Amboy's charter or abandon it for a township form of government. His vote was cast at City Hall in Perth Amboy, New Jersey on March 31, 1870.[11] On a per capita and absolute basis, more blacks were elected to public office during the period from 1865 to 1880 than at any other time in American history including a number of state legislatures which were effectively under the control of a strong African American caucus. These legislatures brought in programs that are considered part of government's role now, but at the time were radical, such as universal public education. They also set all racially biased laws aside, including anti-miscegenation laws (laws prohibiting interracial marriage).[dubious ]

Despite the efforts of groups like the Ku Klux Klan to intimidate black voters and white Republicans, assurance of federal support for democratically elected southern governments meant that most Republican voters could both vote and rule in confidence. For example, an all-white mob in the Battle of Liberty Place attempted to take over the interracial government of New Orleans. President Ulysses S. Grant sent in federal troops to restore the elected mayor. Those who opposed the Fifteenth Amendment argued that it infringed on states' rights. Governor La Fayette Grover, a Democrat, argued that the amendment "deprived the state of the right to regulate suffrage." A Portland newspaper termed it "an odious measure" that had been forced "down the throats of the people of Oregon." The Republican Oregonian, which had five years earlier opposed granting the franchise to blacks, observed that the "few colored men in Oregon" could have but slight political influence and that they were, in any event, generally "quiet, industrious, and intelligent citizens" who would "exercise intelligently the franchise with which they are newly invested." [12] President Grant said that the ratification of the amendment was necessary "to enable blacks to shape their own future at the ballot box." President Grant put forth effort to push the amendment through congress. He asked Nebraska's Governor to call a special session in that state to discuss the issue, and he considered rushing the admission of Georgia and Texas back into the Union in time for spring elections. After the amendment was ratified, Grant issued a proclamation stating it was a reversal of the Dred Scott decision. [13]

However, in order to appease the South after his close election, Rutherford B. Hayes agreed to withdraw federal troops. He also overlooked rampant fraud and electoral violence in the Deep South, despite several attempts by Republicans to pass laws protecting the rights of black voters and to punish intimidation. Without the restrictions, voting place violence against blacks and Republicans increased, including instances of murder. Most of this was done without any intervention by, and often with the cooperation of, law enforcement.

By the 1890s, many Southern states had strict voter eligibility laws, including literacy tests and poll taxes. Some states even made it difficult to find a place to register to vote. Upon the adoption of the Twenty-fourth Amendment in 1962, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections in 1966, all poll taxes and literacy tests were prohibited in all elections.

There was an impressive surge in political participation after the Civil War, due largely to the Reconstruction acts. In southern states, the total number of white registered was about 600,000 while blacks were about 703,400. In the 1870 census, blacks outnumbered whites in terms of total population in Mississippi, Louisiana, and South Carolina. In the first post-Civil War legislature in South Carolina was 87 blacks to 40 whites. There was no other state besides South Carolina that blacks made the majority in the legislature. In the nineteenth century, blacks would hold important positions in government for the first time, such a lieutenant governor, supreme court judge, secretary of state, and treasurer. Between 1869 and 1880, 16 blacks served in Congress: two in the Senate and 14 in the House.[14]

[edit]Adoption

The Congress proposed the Fifteenth Amendment on February 26, 1869.[15] The final vote in the Senate was 39 to 13, with 14 not voting.[16] Several fierce advocates of equal rights, such as Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, abstained from voting because the amendment did not prohibit devices which states might use to restrict black suffrage, such as literacy tests and poll taxes.[17] The vote in the House was 144 to 44, with 35 not voting. The House vote was almost entirely along party lines, with no Democrats supporting the bill and only 3 Republicans voting against it.[18]

States that ratified pre-certification[15]

- Nevada (March 1, 1869)

- West Virginia (March 3, 1869)

- Illinois (March 5, 1869)

- Louisiana (March 5, 1869)

- Michigan (March 5, 1869)

- North Carolina (March 5, 1869)

- Wisconsin (March 5, 1869)

- Maine (March 11, 1869)

- Massachusetts (March 12, 1869)

- Arkansas (March 15, 1869)

- South Carolina (March 15, 1869)

- Pennsylvania (March 25, 1869)

- New York (April 14, 1869)[19]

- Indiana (May 14, 1869)

- Connecticut (May 19, 1869)

- Florida (June 14, 1869)

- New Hampshire (July 1, 1869)

- Virginia (October 8, 1869)

- Vermont (October 20, 1869)

- Alabama (November 16, 1869)

- Missouri (January 7, 1870)

- Minnesota (January 13, 1870)

- Mississippi (January 17, 1870)

- Rhode Island (January 18, 1870)

- Kansas (January 19, 1870)

- Ohio (January 27, 1870)

- Georgia (February 2, 1870)

- Iowa (February 3, 1870)

States that ratified post-certification:

- Nebraska (February 17, 1870)

- Texas (February 18, 1870)

- New Jersey (February 15, 1871)

- Delaware (February 12, 1901)

- Oregon (February 24, 1959)

- California (April 3, 1962)

- Maryland (May 7, 1973)

- Kentucky (March 18, 1976)

- Tennessee (April 8, 1997)

[edit]See also

- 40 acres and a mule

- Ballot access

- Voting Rights Act

- Voting rights in the United States

- Voter suppression

- Gomillion v. Lightfoot

- Women's suffrage

[edit]References

- ^ "The Constitution: Amendments 11-27". Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- ^ Rice v. Cayetano, 528 U.S. 495 (2000)

- ^ The Constitution of North Carolina. State Library of North Carolina. Retrieved 2008-04-16.

- ^ Dred Scott v. Sandford, Curtis dissent. Legal Information Institute at Cornell Law School. Retrieved 2008-04-16.

- ^ The Fifteenth Amendment And "Political Rights"

- ^ a b Congressional Globe, 40th Cong., 3d Sess (1869) pg. 1318

- ^ Gillette, W. (1969). The Right to Vote. pp. 71.

- ^ Foner, Eric (2002-02-05). Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877. Harper Perennial Modern Classics. pp. 448. ISBN 978-0-06-093716-4.

- ^ http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/general-article/grant-fifteenth/

- ^ 15thamendment.harpweek.com

- ^ [McGinnis, William C. "Thomas Mundy Peterson, First Negro Voter in the United States Under the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution." Privately published, 1960]

- ^ http://www.oregonencyclopedia.org/entry/view/15th_amendment/

- ^ Max J. Skidmore, "The Presidency of Ulysess S. Gnrat: A Reconstruction" White House Studies volume 5, number 2, pages 255-270 (2005)

- ^ Kaushi, R. P.. "The Issues of the Political Rights of the Blacks: The Formative Period, 1865-1877". Indian Journal of American Studies: 58-64.

- ^ a b Mount, Steve (January 2007). "Ratification of Constitutional Amendments". Retrieved February 24, 2007.

- ^ Gillette, W. (1969). The Right to Vote. pp. 75.

- ^ Gillette, W. (1969). The Right to Vote. pp. 76.

- ^ Gillette, W. (1969). The Right to Vote. pp. 73–74.

- ^ Rescinded ratification on January 5, 1870, and re-ratified on March 30, 1970

[edit]External links

- Fifteenth Amendment and related resources at the Library of Congress

- National Archives: Fifteenth Amendment

- CRS Annotated Constitution: Fifteenth Amendment

| ||

| ||

No comments:

Post a Comment